Many luthiers contact me each month inquiring about fanned fret guitars, ranging from general questions like “What is a fan fret guitar?” or “How to make a fanned fret guitar?” all the way to questions about the finer details like how to choose the scale lengths and the physics of why this even matters.

There just isn’t much reliable info out there about the topic of multi-scale or fanned fret guitars, and even less about how it actually works and how to get the best results from using it. I’m writing this article to give you the answers to many of those questions and more.

Answering those questions for myself was a daunting process of experimenting, requiring years of trial and error to get to a point where I was confident enough to try it on one of my guitars, but when I did, it transformed the way I think about and build guitars forever (it even improved my single scale guitars).

Many years later, guitars with fanned frets are some of my favorite guitars to build because of the resulting expanded tonal range and improved playing ergonomics—not to mention the cool and modern look.

The process of designing and building a fanned fret guitar doesn’t need to be so difficult or scary for you, though. With the right information, you can confidently begin designing and building your own fanned fret guitar in no time.

In this article, we’ll cover the key concepts and core ideas you’ll need to begin designing and building your own multi-scale guitars that I hope will give you a head start and a far better chance of getting great results on your next guitar.

The first step is to take a quick look at some background of multi-scale or fanned fret instruments, and you might be surprised to find out that it is certainly not a new idea.

A Very Brief History Of Multi-Scale Instruments

The concept of the multi-scale musical instrument (one in which each string has its own scale length) is not new by any means. It is commonly employed in many instruments, such as the piano, harp, and many others. This multi-scale arrangement applied to a fretted instrument has become known today as “Fanned Frets” or simply “Fan Frets”.

According to Wikipedia it first appeared in the 16th century Orpharion, a variant of the cittern, as well as the Bandora, which is a late 16th-century instrument with a longer string length for its bass strings than for its trebles.

The first patent for a fingerboard of this design was filed by E. A. Edgren in 1900. Others have used and patented different versions of this. However, we owe thanks to Ralph Novak for his research and for applying the multi-scale arrangement to a modern guitar.

Modern Fanned Fret Resurgence

One of the best illustrations I have heard regarding the critical influence of the scale length on guitar tone is from Ralph Novax, the father of the modern fan fret resurgence. He described this in his Fan Fret Technical Lecture as follows:

“The familiar example might be the “Strat vs. Les Paul” comparison: as stock instruments, they have distinctly different voices. We could put the Les Paul pickups in the Strat and vice-versa, then take the screws out of the Strat neck and glue it in, and break out the Les Paul neck and screw it back in. Voila! The Strat still maintains much of its clear, cutting quality, although a bit “fatter,” and the Les Paul still has a round attack and mushy bass, although “thinner.” We’ve discovered that the pickups and construction can’t override the tonal effects of scale length. The upper partials present in the harmonic structure of the longer scale Strat string tone give it a cutting clarity that distinguishes it from the sweet, round, lower partials that dominate the shorter scale Les Paul string tone.”

I have found this to be very accurate, and once you grasp the tonal implications of the guitar scale length, it can be a powerful tool in your arsenal of guitar-making weapons. You can use different scales to get just the right tone for each player you build a guitar for, even if you are not using fanned frets.

Of course, the scale length is just the beginning of all the design elements that go into a guitar, but starting out with the right scale makes the rest of the process that much easier.

How Scale Length Effects Guitar Tone

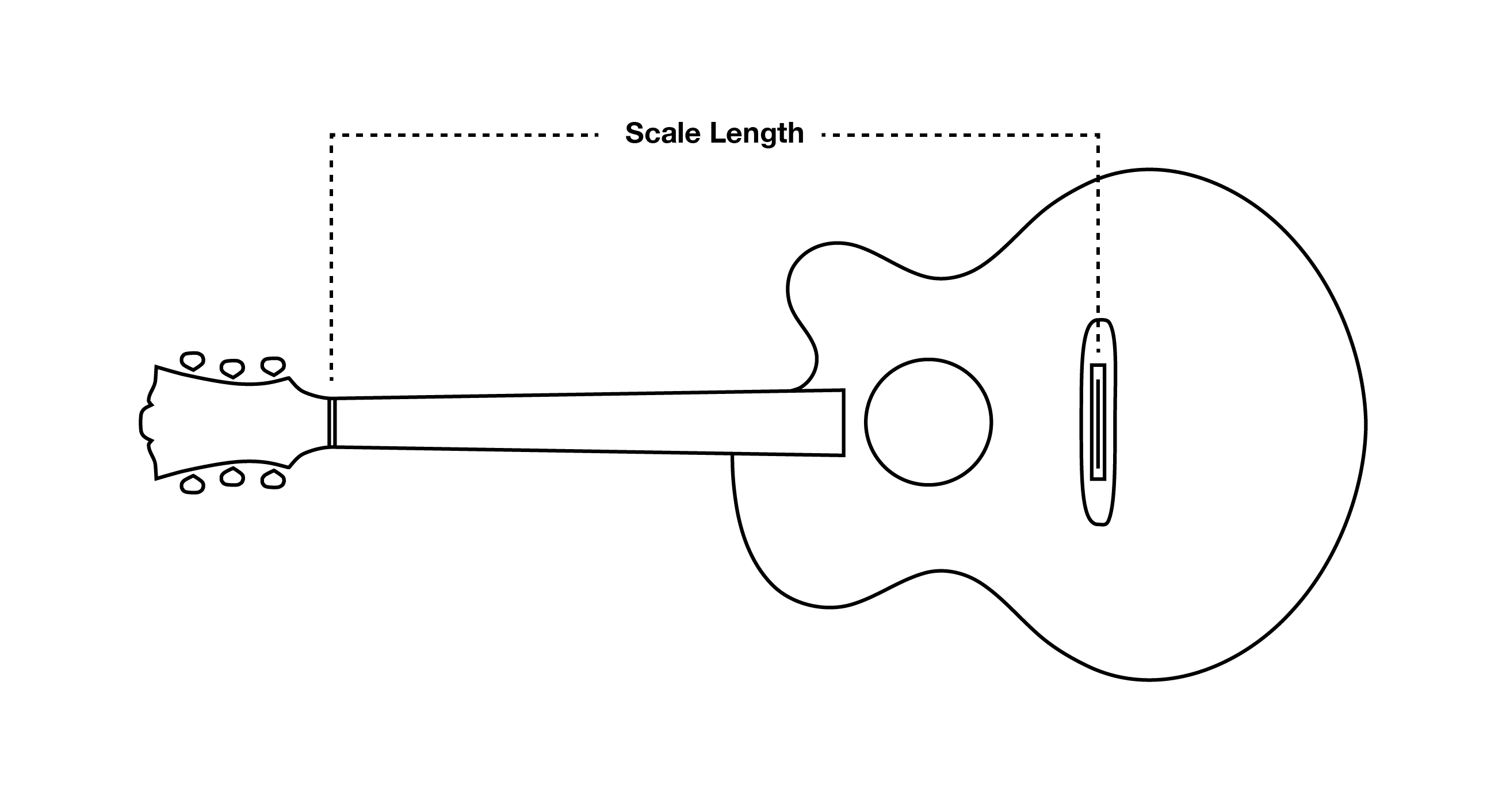

The scale length (or the distance measured from the nut to the saddle; the vibrating length of the string) of any musical instrument is probably the most commonly overlooked element of design when engineering the “voice” or “tone” of a guitar. The scale length is responsible for regulating the initial input of vibration energy that is injected into the guitar’s top, setting the entire system in motion. We talk about this in great detail in our online course [Guitar Physics and Design] and also in my physical book [The Art Of Lutherie].

Everything after that point can only be filtered or somehow modified, but not added to in any large way. While the myriad of components and other variables of the individual guitar will play a large role in determining its final voice, the scale length will still set the main parameters that the rest of the system will have to work within.

That’s why starting with the best scale length (or even building multi-scale guitars) can be such a useful tool in helping you get the perfect tone and feel from each guitar you build.

How To Choose The Scale Lengths For Your Fanned Fret Guitar

Below is a video sample taken from the course: “How To Build A Fanned Fret Guitar,” which discusses my approach to choosing the best scale length combination for a multi-scale guitar. Be sure to leave a comment on this post or reach out if you have questions or need some help.

Learn more about the complete Fanned Fret Guitar Course by clicking the button below.

Why Scale Lengths Matter: String Tension & Mass

As we explore the importance of scale length in establishing the guitar’s basic tonal properties, there are many factors that we have to think about, which are at play with the scale length to give the guitar its basic tonal or harmonic envelope. Two of those factors are string tension and mass.

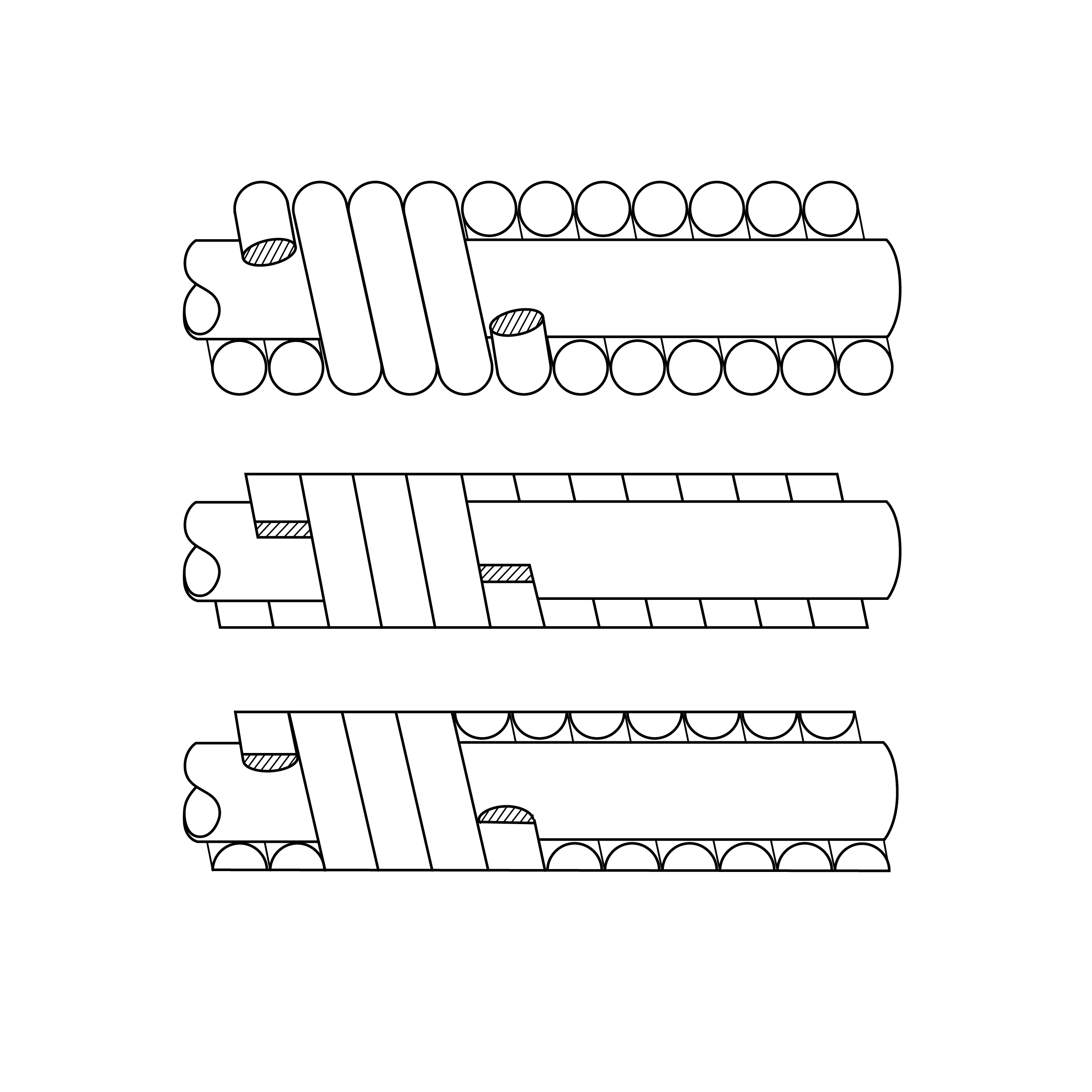

Without getting into the mathematics of it (see this link for further reading), the basic premise is that each time we increase the diameter of the string, thus increasing its mass, we also increase the amount of tension required to bring it to pitch. This is one reason why players most often use larger gauge strings for the lower notes of the guitar.

If we used the same plain steel .010 high E string for the low E, I’m sure you could imagine, it would not sound very good. It wouldn’t have enough tension to sound in the overtone series, and it also wouldn’t have enough mass to give it any volume.

So having more mass (larger diameter) is better for a string tuned to a lower pitch, but we also have to keep in mind that this added mass and tension brings with it two side effects. The first is that the extra mass helps the string get more volume and clarity, but the second side effect is increased stiffness. As the stiffness is increased, the string’s ability to divide into complex high-frequency nodes decreases.

One reason we commonly wrap the lower strings is to try to increase mass but, at the same time, add as little stiffness as possible. Wrapping the thinner core wire is a really great idea that helps us get a much better tone for our guitars with little extra stiffness. That stiffness is what causes us to add what we call [compensation] to the saddle. Can you imagine how much compensation we would need if we used a .053″ plain steel string!?

The next part is really important because it not only helps us understand the fanned fret guitar design and scale length phenomena that are happening within it but here’s the best part, if you take time to think about it more, it can totally change the way you build guitars of any design.

In this next section, we will look at how stiffness and mass affect the ability of the guitar string to divide into different overtones, and guess what?

The other parts of the guitar, like the top, behave this way too!

Getting a firm grasp on this concept helped me understand WHY I was getting the results I perceived from my experiments in bracing and other guitar design elements and was instrumental (pun intended) in empowering me to push my designs further and get better results.

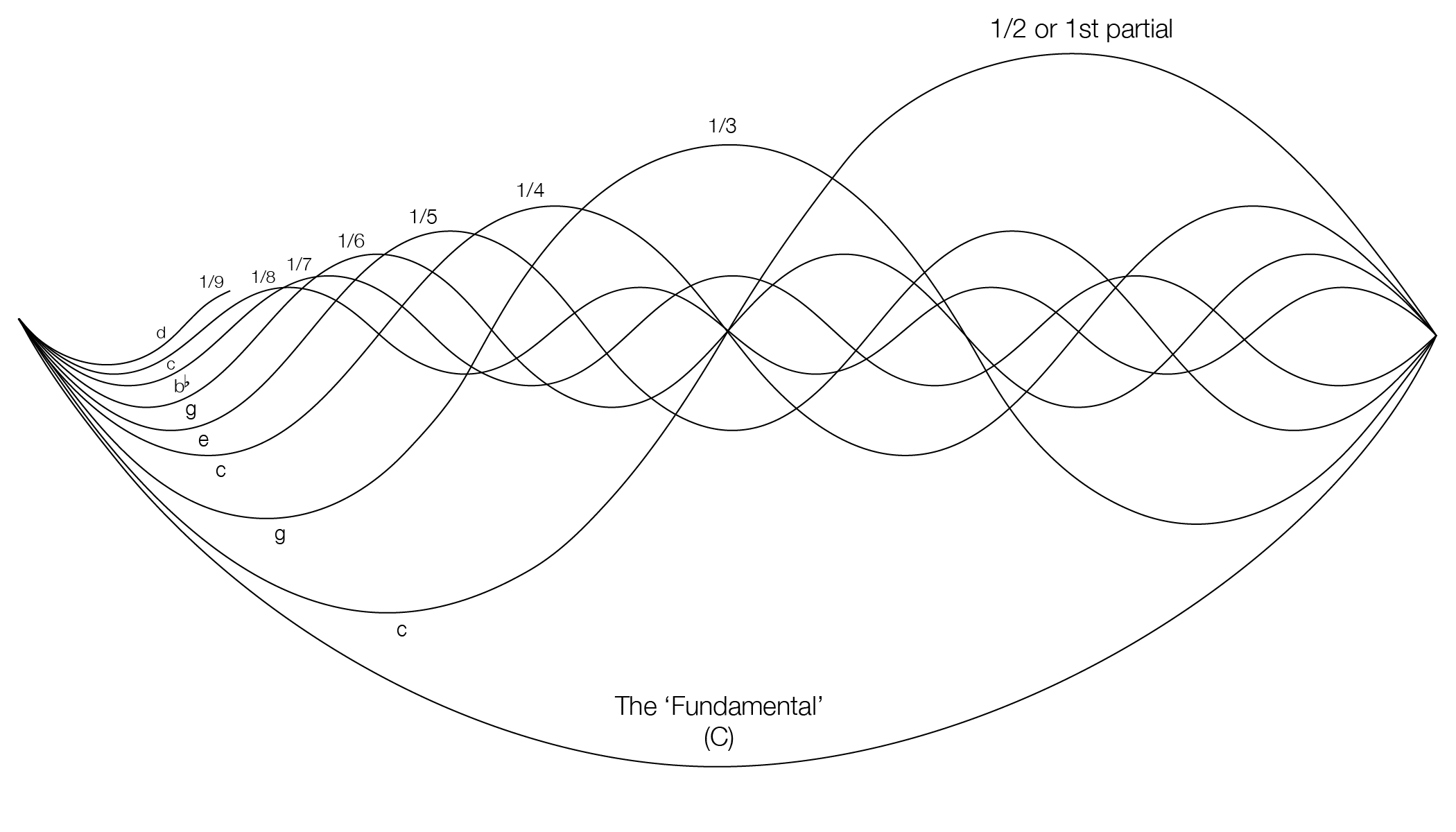

The Physics Of Better Tone: Thickness, Folding, & Overtones

My good friend and mentor, luthier Gila Eban explained something like this to me years ago by using the analogy of a dishcloth. If you start with a regular dishcloth and fold it in half, it’s very easy and folds nicely. Fold it again, and it is still OK, continue folding it in half again and again, and each time, it becomes in effect, thicker. With that extra thickness, its ability to fold gets diminished and requires more energy, or it simply isn’t possible to fold again. This type of folding is akin to a string as it “folds,” or divides, into smaller and smaller sections that make up the overtone series of the string’s fundamental note and give the note its tonal and harmonic character.

That helps to understand why changing the scale changes the sonic fingerprint of the guitar, but that’s not all! Remember what I mentioned earlier about the other parts of the guitar? The guitar top, for example, has to fold or divide into different parts, much like the string. Think about this when you are laying out your bracing and thicknessing the top plate. A thinner top will divide or fold more easily, resulting in more audible high frequencies. That thin top will have less resistance to vibrating in smaller pieces in order to accommodate the shorter high-frequency wavelengths. Or in other words, it will be more efficient in that regard for high-frequency energy.

Of course, there are many variables to consider, and experimenting is important to get a sense of how much control you have and how to balance it out. But now that you understand this concept, you can be more intentional in the way you “EQ” that signal coming from the strings (and your scale length(s) you chose) as it is processed by the guitar system you have created and eventually output as audible sound.

OK, the whole guitar top thing was a little off the subject of fanned frets, but I couldn’t resist sharing that with you because that concept was a real game-changer for me. So let’s get back on track; here is a little recap: We have to consider the tone we want from our guitar, then choose the scale length that best fits it. All the while keeping in mind the effects of string gauge, tension, and mass. Pretty simple.

The Single-Scale Problem

The problem is that we usually have six strings, each with a different set of the above-mentioned criteria. Using only one scale length causes us to compromise overall. Let’s say I decide that for my new client, the best scale length to get the sound he wants for a steel string high E might be 25″, but he also wants to tune down to a dropped D on the low E string. That D will sound floppy and muddy at 25″ (with a standard gauge string). OK, no problem, let’s use a 26″ scale then, and the dropped D will be great; but now at 26″ the high E sounds like a banjo and could possibly shatter a wine glass or something with its shrill piercing voice!

This is where the fanned fret (multi-scale) type of guitar comes to the rescue.

The Fanned Fret Guitar Solution

If we build fanned fret or multi-scale guitars, we can specifically choose a different scale for each string that perfectly suits our needs and allows us to incorporate all of the necessary criteria we have without compromising on any of the strings.

With fanned frets, we can get that great mellow treble at a 25″ scale AND that clear, powerful bass note at a 26″ scale.

Now that you understand this, it opens up limitless possibilities with mixing and matching scale lengths on your guitars to get different results for players to suit their needs, styles, alternate tunings, and more.

Other Benefits: Better ergonomics

“But what about playing the thing…? or Is it really comfortable to play those fanned fret guitars?” you might ask.

Yes, it is actually more ergonomic than playing a standard single-scale instrument! Look down at your hand and spread your fingers as wide as you can. Do you notice how your fingers are actually fanned out, emanating from a common point?

This resembles the angles on a well-thought-out and implemented fanned fret guitar fingerboard and, in most cases, requires less of that awkward wrist tweaking we guitar players all hate as we strain to make our “fanned fingers” go in parallel lines perpendicular to the strings like a traditional single scale fingerboard.

Want To Build A Fanned Fret Guitar?

When it comes to building a fanned fret guitar, there are definitely some critical points to consider when laying out and designing your fanned fret fingerboard that can make or break the comfort and playability of the guitar. Building a successful fanned fret guitar requires far more than just picking a couple of scales and slapping them on there, but with the right information, the process can be easy and fun.

That is why I created my online course, “How To Build A Fanned Fret Guitar,” to give you everything you need to add fanned frets to your next guitar and get great results.

Learn more about the complete Fanned Fret Guitar Course by clicking the button below.

Have Questions Or Need Some Help About Fanned Frets?

If you have questions or need some help, here are four resources to get you started out in the right direction on your fanned fret guitar project:

- Send me an email, and I’ll do my best to help

- Check out the video above on how to choose the best scale length.

- Check out my online course: How To Build A Fanned Fret Guitar.

- Use the FAQ section below:

Can you use a standard packaged string set for a fanned fret guitar or do you need a custom set of strings?

Hi Jack, That’s a great question! Yes, for most fan fret guitars, you can still use a standard set of strings. If I am going to do extremely long scale lengths for the low strings, I will often check the length of the strings I intend to use first to make sure they are long enough, but so far, they have always been fine. Let me know if you have any other questions I can help with.

Hi Tom,

That’s an in-depth explanation, well-done!

And, thank you for the mention!

I had to retire due to loss of eyesight in 2014, and I’m pleased that luthiers like you are continuing to offer multi-scale instruments, growing your business with the concept.

Ralph Novak

Hey Ralph, thanks so much! Your work has made an enormous impact on so many of our lives. When I first discovered your article that I linked, it opened my eyes (and ears) in a new way that deepened my understanding and brought my guitars to a higher level. I’ll always be grateful that you shared your knowledge and skills with us, and I’m doing my best to pass on these things to future generations, too.