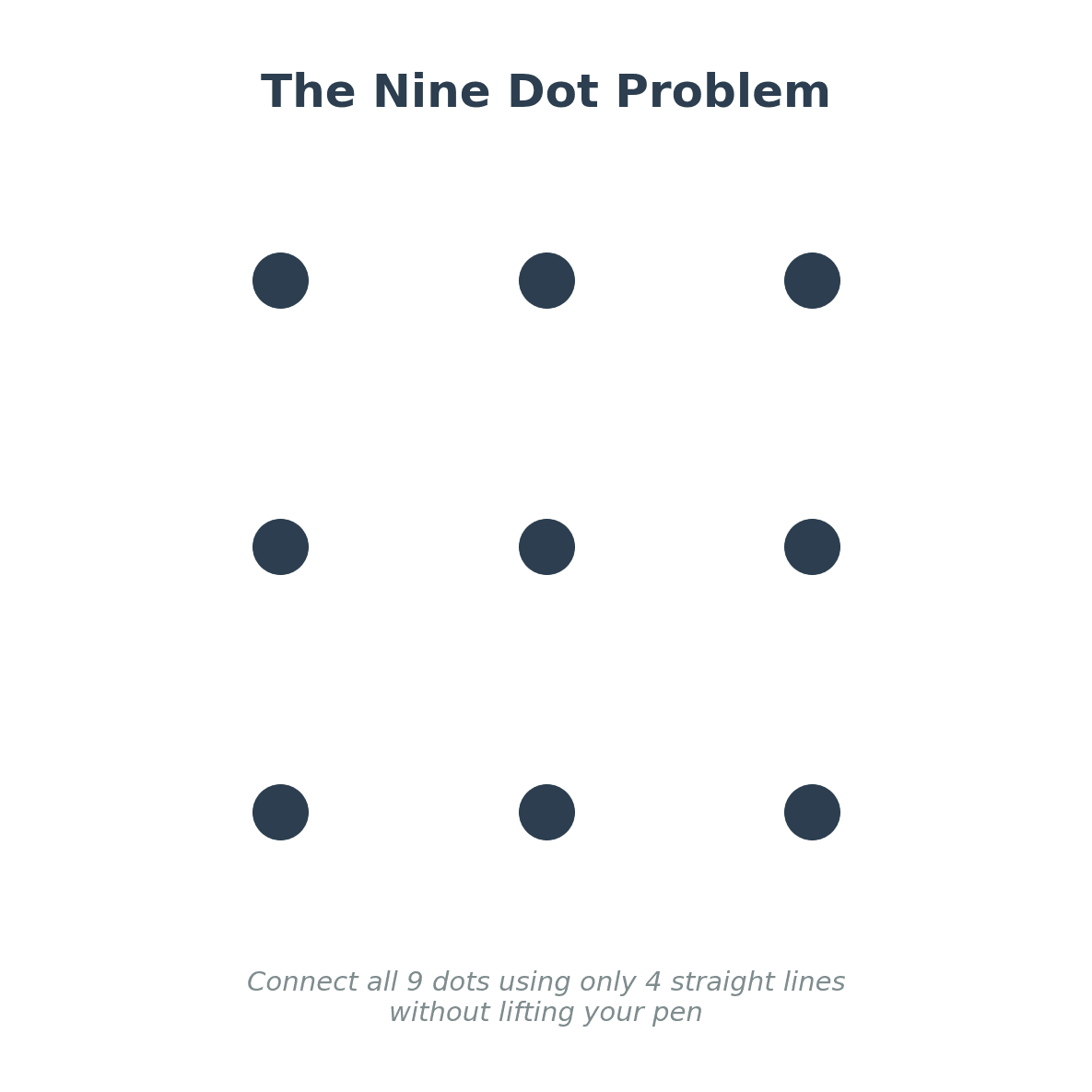

Not the real ones — the ones we don’t even realize we’ve created for ourselves. It started when I came across an old puzzle. You might have seen it before. Nine dots arranged in a square — three rows of three.

The challenge is simple: connect all nine dots using only four straight lines, without lifting your pen.

Most people can’t do it. They try every combination. They get frustrated. They assume there’s some trick they’re missing.

But there’s no trick. The solution is actually straightforward — once you see it.

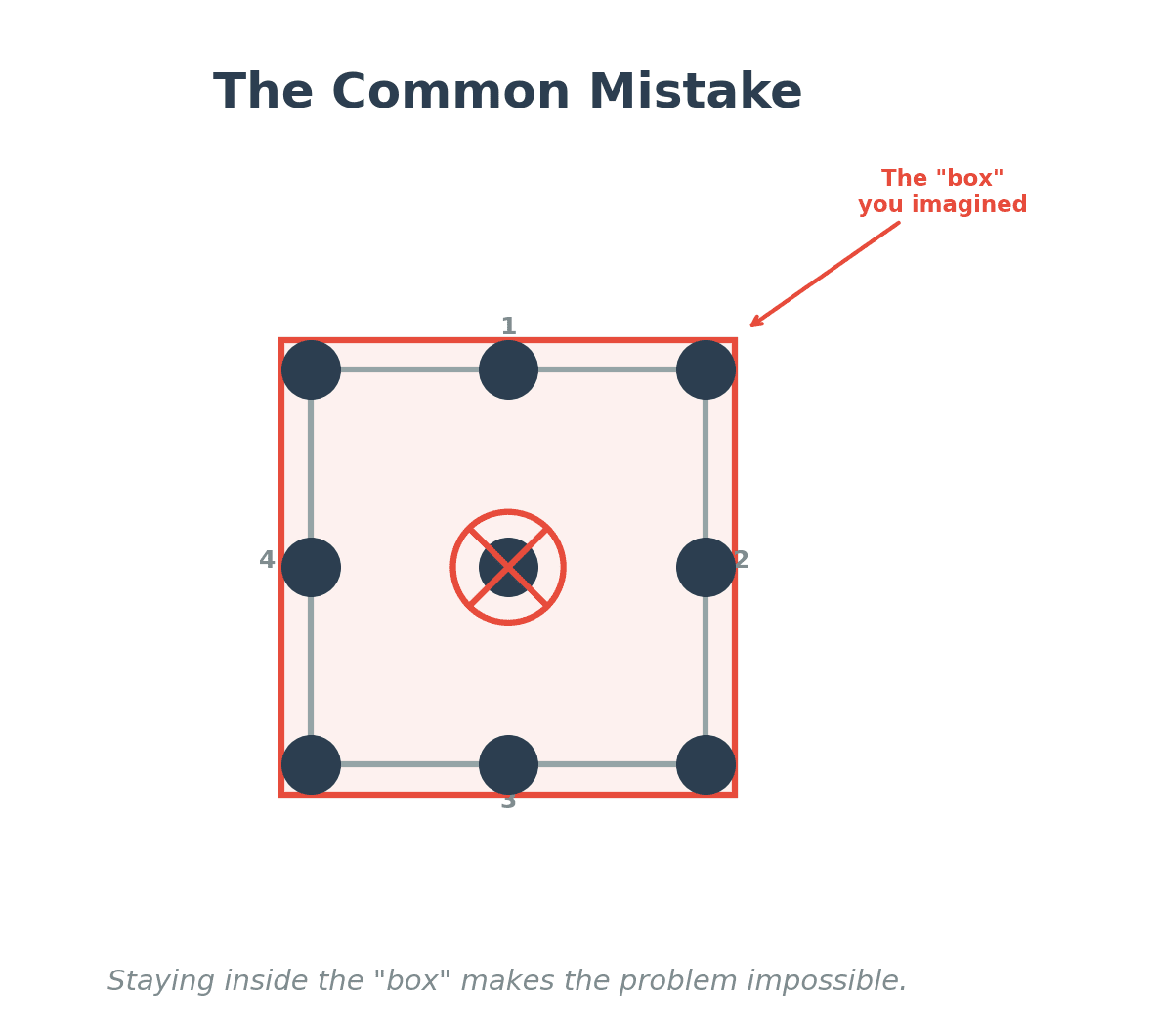

The problem is that almost everyone imposes a rule that doesn’t exist. They assume the lines have to stay inside the square formed by the dots.

They see a boundary that was never actually there.

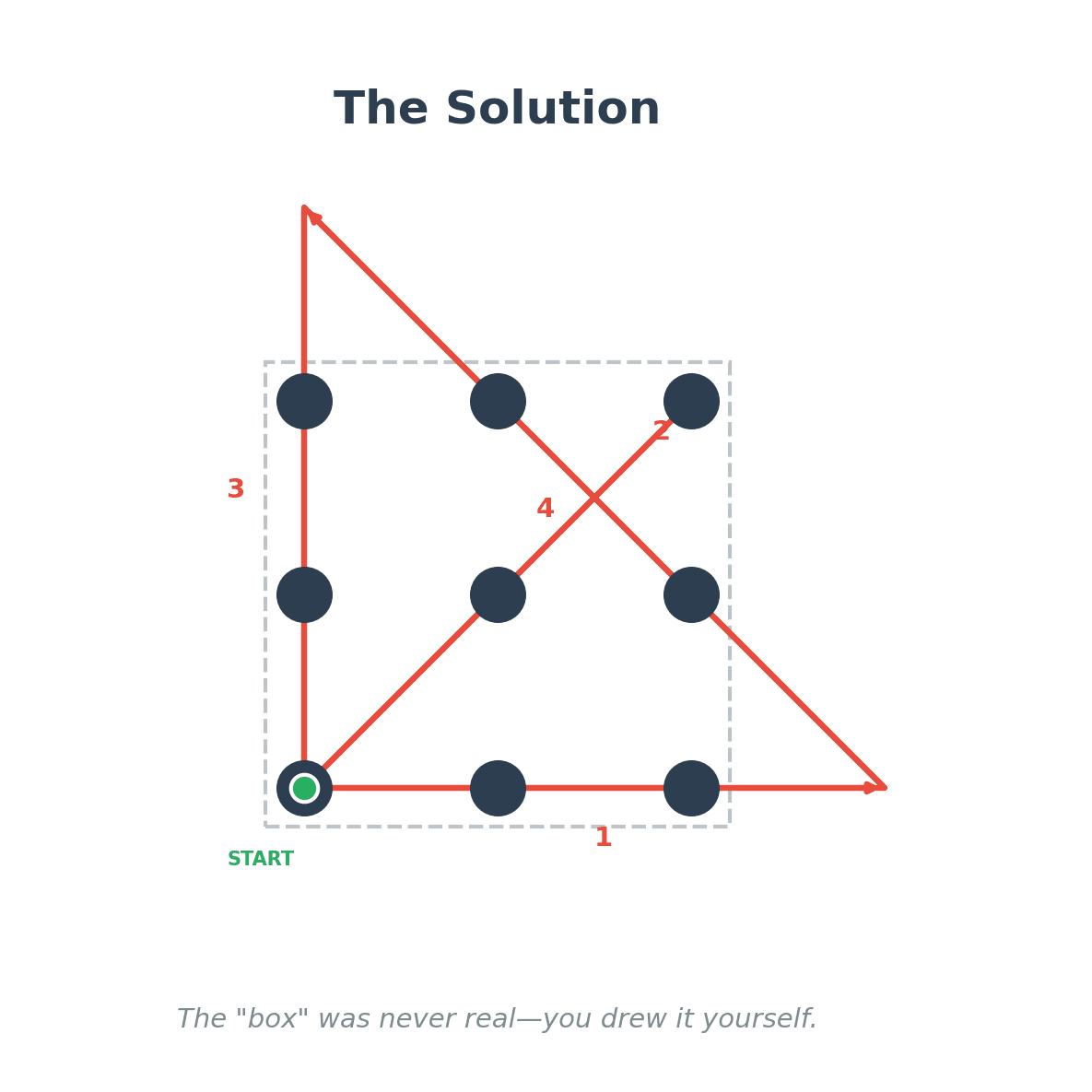

The moment you realize you can extend your lines beyond the dots — outside that imaginary box — the solution becomes obvious.

This puzzle is believed to be the origin of the phrase “Thinking Outside the Box.”

Here’s the thing that’s been sitting with me:

The box isn’t real. You drew it yourself.

Nobody told us to stay inside. Nobody said the edges of the dots were walls. Our mind created the constraint — and then we struggled against something that was never actually there.

I see this all the time in guitar building. And honestly, I’ve lived it.

When I was just starting out, I didn’t have all the tools.

I didn’t have a shop.

I didn’t even really know how I was going to pull this off.

Around that time, I walked into a music store looking for guitar-building books. When I asked about them, the guy behind the counter mentioned that their luthier, Mike, had built an archtop before and went to get him.

That got my attention — and gave me an idea.

When Mike came out to see me, I said, “Do you think it would be okay if I paid you twenty dollars a week and you let me come use your workshop one night for an hour or two? Kind of like a guitar lesson?”

He said sure.

So that’s what we did. I didn’t have access to his shop on my own — he was there, working on other things, keeping an eye on me. And when I had a question, I could just ask, “Hey Mike, what do I need to do in this situation?”

And those seemingly unimportant little questions added up to a big difference.

So, I didn’t have a real workshop. I didn’t have the proper tools. But I found a way to take the next step. And that arrangement taught me more than just technique — it showed me that the walls I thought were there weren’t actually walls.

Even after I started building professionally, my tools were far from ideal.

One of the first chisels I used was a quarter-inch chisel my dad was about to throw away. He’s a framing carpenter — works hard, not exactly gentle with his tools. Most of them were pretty well destroyed.

This one had a chip taken out of one side. It was already small, and now it was damaged.

I said, “I’ll take it.”

I sharpened it the best I could and just figured it out. I had to take more cuts. Be more precise with my positioning. Work around the chip. After a while, it became no big deal.

I made quite a few guitars with that chisel.

Looking back, I thought I had a tool problem. What I actually had was a *thinking* problem. I was inside a box I didn’t even know I’d drawn. I assumed I needed all the right tools before I could start.

That assumption wasn’t true.

I see this with workspace too.

People convince themselves they need a dedicated shop before they can begin. Fancy tools, a proper workbench, factory-grade dust collection — the whole setup.

But I know builders who’ve made beautiful instruments on a kitchen table. In garden sheds. In garages with concrete floors and no insulation.

A guitar doesn’t know if it was built in a two-car garage or on a folding table in a spare bedroom. It only knows if it was built with care.

Yes, you’ll want to manage things like dust and humidity Yes, a stable surface helps. But those are problems to solve — not walls that stop you from starting.

So much of what holds us back in this craft isn’t real.

It’s stories we’ve absorbed, from forums, from YouTube, from comparing ourselves to builders with decades of experience and $40,000 shops.

We think we need more tools, more space, more knowledge, more certainty before we can begin.

But often, what we actually need is to notice the box we’ve drawn around ourselves, and realize we’re allowed to step outside it.

The constraints holding you back might not be real. They might just be assumptions you haven’t questioned yet.

The box isn’t real. You drew it yourself.

And you can erase it.

Sapere Aude. Creare Aude.

—Tom