On a blustery day In the fall of 1997, I rushed into a small bookstore searching for a special book I had heard about, one that could help me make my dream a reality, it was a book that could show me how to make an archtop guitar! It was almost magical as I slid the book off the shelf and looked at it there in my hands for the first time; “Making An Archtop Guitar” by Robert Benedetto. I had seen and heard his amazing guitars before…they were the stuff of legends for me, a college jazz guitar major who couldn’t afford to buy an archtop and dreamt of building one of his own. I will never forget that day, I read the book from cover to cover in one sitting and as I closed the last page, I knew at that moment my life would never be the same. Without Bob’s generosity and courage to share his hard-won secrets and teach the rest of us how to make an archtop guitar through his book, I don’t know if I would be here writing this to you today, and I will forever be grateful to him for it.

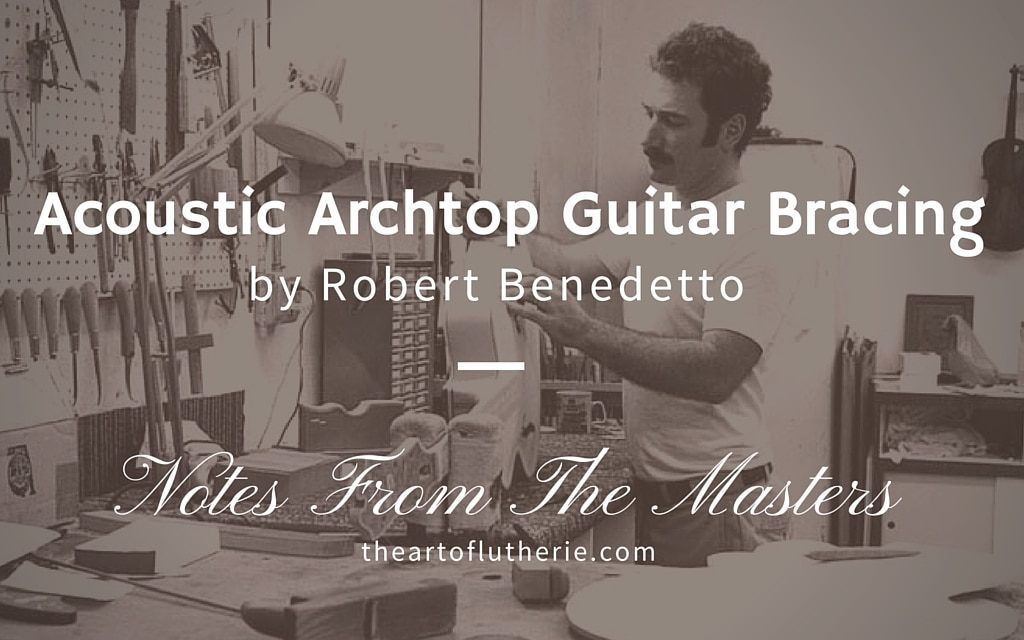

In this inaugural issue of “Notes From The Masters”, a new series featuring special featured articles from world-renowned master luthiers, I am honored to share with you the first guest luthier here on rpd-3f25.ue1.rapydapps.cloud: Robert Benedetto. In his article he shares with us valuable insights from his 47+ years of experience on how to choose the right bracing patterns, woods, and more for acoustic archtop guitars. Enjoy! – Tom Bills

Acoustic Archtop Guitar Bracing

by Bob Benedetto

Archtop Guitar Bracing Patterns

Most makers and players would agree that, in general, there are two preferred bracing patterns: Parallel bracing, which results in a louder, more punchy voiced guitar, and X bracing, which may best be described as being warmer and with more balance between highs and lows. The latter usually (but not always) is better suited for the modern player.

Most makers and players would agree that, in general, there are two preferred bracing patterns: Parallel bracing, which results in a louder, more punchy voiced guitar, and X bracing, which may best be described as being warmer and with more balance between highs and lows. The latter usually (but not always) is better suited for the modern player.

Choosing Wood For Bracing

All else being equal (and it never is), the above concise summation is a pretty good reference when buying or making an acoustic archtop guitar.

But it doesn’t end here. There are many variables that can affect the outcome; one of course is wood selection. When selecting wood for bracing stock, a good rule of thumb is to use the same criteria used when selecting wood for the guitar’s top. For the top, any conifer will do; spruce, cedar, redwood, pine, fir, larch and probably a few others all work well. Even if we were to compromise stiffness or weight by using a lesser grade of wood for the top, with the proper bracing, the acoustical outcome can still be first rate.

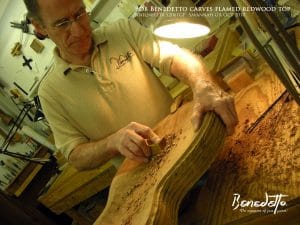

My own preference, regardless of the wood used to carve the top, is select European spruce … lightweight, quarter-sawn and stiff. Even a guitar with a soft, mushy redwood top will have a beautiful, rich voice if it’s braced properly with stiff, lightweight European spruce. The same would apply to any other conifers used for the top.

My own preference, regardless of the wood used to carve the top, is select European spruce … lightweight, quarter-sawn and stiff. Even a guitar with a soft, mushy redwood top will have a beautiful, rich voice if it’s braced properly with stiff, lightweight European spruce. The same would apply to any other conifers used for the top.

- Lightweight braces have an advantage because the lighter bracing contributes to a lighter instrument (splitting hairs!), and lighter instruments have greater acoustic capabilities.

- Quarter-sawn stock will allow the maker to sculpt the braces optimally narrow and/or low profiled to maximize their function acoustically and structurally.

- Stiff braces transmit the string’s vibrations to the top with lightning speed, which results in a more responsive instrument.

Spring Fitting & Tension

Adding a little spring to the bracing as is done on the violin or cello is a nice touch. Spring adds tension to the top, and a top under tension is louder than it otherwise would be. The disadvantage to adding spring to braces is that after a period of time (which varies from wood to wood), the braces give way to the shape of the curved surface that they are glued to, and lose their spring. Loss of spring means loss of tension, which will have a negative effect on the voice of the instrument. A guitar that sounded remarkable from the first day it was strung will likely lose some of that magic as the now relaxed braces no longer add tension to the top. ( For the Art Of Lutherie tutorial on how to fit archtop braces – click here)

Other Archtop Bracing Possibilities

There is no question about the popularity and acceptance of both parallel and X bracing. But there are also many other possibilities. Elmer Stromberg, Carl Albanus Johnson and Bill Barker all used one diagonal brace. All three made wonderful sounding guitars with the same level of acoustical refinement as D’Angelicos, Gibsons and Epiphones of the same period. Many years ago while working on an old 16” non-cutaway D’Angelico, I noticed it had one brace located directly under, and in-line with the bridge … and the guitar sounded great! I would have never thought one, simple, transverse brace would work so well. On a few occasions I have even braced tops with variations of traditional classical guitar fan bracing. That works too.

There is no question about the popularity and acceptance of both parallel and X bracing. But there are also many other possibilities. Elmer Stromberg, Carl Albanus Johnson and Bill Barker all used one diagonal brace. All three made wonderful sounding guitars with the same level of acoustical refinement as D’Angelicos, Gibsons and Epiphones of the same period. Many years ago while working on an old 16” non-cutaway D’Angelico, I noticed it had one brace located directly under, and in-line with the bridge … and the guitar sounded great! I would have never thought one, simple, transverse brace would work so well. On a few occasions I have even braced tops with variations of traditional classical guitar fan bracing. That works too.

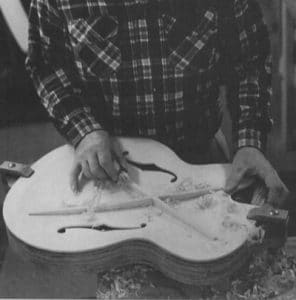

It didn’t take me long to realize that the bracing pattern is only one aspect of the acoustic archtop design. I experimented a lot with both parallel and X bracing and varied each in length and profile. I increased and decreased the space between the parallel braces and changed the angles. And I did the same with the X brace … kind of like opening and closing scissors. After a few years of that, I was convinced that when carefully executed, that almost any pattern would work. I still believe the rule of thumb is accurate (as described in paragraph 1), but it’s often hair splitting.

What I found to be a most interesting phenomenon is that regardless of the bracing pattern, at about the 15-year mark of making guitars, my guitars sounded consistent. Of course there were exceptions, but in general, they all sounded like they were related. It seems, as with many other repetitive tasks, our instincts take over, and we improve.

Final Thoughts & Advice

So what does all this tell us? That, although a bit subjective, almost any bracing pattern will work? Or maybe we are still in the evolutionary stages of acoustic archtop design and have not yet arrived at the optimum bracing system. Who knows? For now I’m convinced that an experienced maker with good instincts can intuitively locate and fit braces in almost any pattern and achieve the desired results.

My advice to aspiring archtop makers, whose intention is to sell guitars and make a living at it, is to consider marketability when choosing your bracing pattern. Both parallel and X bracing are the industry standards. Anything outside of that may be a tough sell and there is no need to put yourself at a disadvantage in such a competitive market.

……. or, maybe you’re the one who is going to make the final bracing statement. Go for it!

– Bob Benedetto

Now Check Out The Art Of Lutherie’s Step By Step Tutorial On Fitting Archtop Guitar Braces

Click Here: Archtop Guitar Bracing Tutorial

About The Author

Robert Benedetto is widely acknowledged as today’s foremost maker of archtop guitars. Over a prolific 47 year career, he has personally handcrafted nearly 1,000 instruments, including 500 archtops. “My roots are in jazz guitar. It’s been my love and my focus since Day One.”

Robert Benedetto is widely acknowledged as today’s foremost maker of archtop guitars. Over a prolific 47 year career, he has personally handcrafted nearly 1,000 instruments, including 500 archtops. “My roots are in jazz guitar. It’s been my love and my focus since Day One.”

He crafted guitars for noted players Bucky Pizzarelli, Chuck Wayne, Joe Diorio and Cal Collins, and, later, Johnny Smith, Jack Wilkins, Ron Eschete, Martin Taylor, Howard Alden, John Pizzarelli, Andy Summers, Jimmy Bruno and Kenny Burrell (collectively known as “The Benedetto Players”). His guitars appear on countless recordings, TV & film soundtracks, in videos, books, magazines, museums (including the Smithsonian Institution) and concerts worldwide. – To Read Bob’s full bio: Click Here

To See Bob’s work and learn more about Benedetto Guitars Click Here

Trackbacks/Pingbacks